“When I Let Go of What I Am, I Become What I Might Be”: Understanding Path Dependency and Avoiding Organizational Lock-In

The Brief: Path dependency explains how organizations become locked into established ways of thinking, acting, and deciding—often without realizing it. What begins as a successful decision-making framework can become rigid over time, limiting the organization’s ability to adapt. This rigidity, when reinforced by routines, systems, and past successes, leads to organizational lock-in.

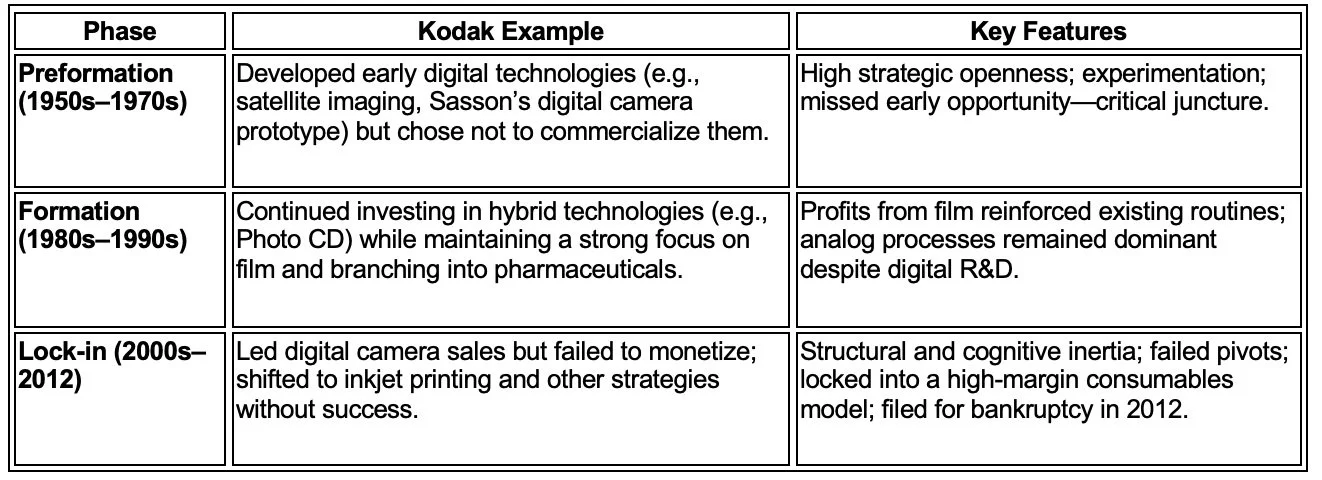

The theory outlines three phases: 1. Preformation Phase: organizations operate with wide strategic openness, 2. Formation Phase: routines repeat and self-reinforcing mechanisms emerge and 3. Lock-in Phase: the organization becomes constrained by legacy systems and thinking, even when better alternatives exist

To avoid lock-in and maintain strategic flexibility, organizations should: • Embed strategic consciousness throughout the organization, • Operationalize routine reflection to sustain objectivity, • Design for both elasticity and efficiency in systems and structures, • Experiment beyond the current business model through pilot teams and concept pipelines and • Reframe disruption as an opportunity to reset strategy and assumptions

Understanding Path Dependency

“When I let go of what I am, I become what I might be” is a quote attributed to the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu. Known for his work Tao Te Ching, Lao Tzu emphasized the importance of how to live in harmony with the universe and the natural way of life and embrace uncertainty. While the quote applies to personal growth, it also serves as a metaphor for organizational renewal—and a lens through which we can examine the theory of path dependency.

The concept of path dependency is closely associated with Paul David’s 1985 paper Clio and the Economics of QWERTY, in which he presents how the QWERTY layout of the keyboard illustrates how historical events can lock organizations into suboptimal technologies or practices through increasing returns and self-reinforcing processes. Despite the availability of better alternatives, organizations may persist with inefficient decisions due to early successes, embedded routines, or institutional norms. Contributors to this theory include Brian Arthur, Douglass North, Kathleen Thelen, and James Mahoney.

At its core, path dependency refers to organizational rigidity—when past decisions constrain current choices. This “stickiness” is reinforced through habit, infrastructure, and belief systems. Over time, the organization becomes locked into a specific path, often reinforced by decision-making biases like confirmation bias or escalation of commitment. Lock-in does not always result from inertia; it often stems from once-successful strategies becoming deeply institutionalized.

We can think of this as a form of structural and cognitive entrenchment: a kind of programming where self-reinforcing mechanisms—such as financial gains or reputational rewards—reduce openness to alternatives. Switching becomes difficult not just operationally but politically, as changes often require shifts in power, mindset, or identity.

A quote from C.S. Holling’s 1973 article Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems underscores the paradox:

“It is at least conceivable that the effective and responsible effort to provide a maximum sustained yield from a fish population or a non-fluctuating supply of water… might paradoxically increase the chance for extinction.”

Phases of Path Dependency

Phase I: Preformation: The organization has a relatively wide range of options available. Institutional history, e.g., routines, culture and policies, does have influence, however, there is no set of defined criteria that is used to make decisions. It is in this phase that decisions can initiate a specific trajectory or path.

Phase II: Formation: The organization starts to narrow its focus and direction, and the range of options becomes limited. Positive outcomes start to emerge from past decisions. Self-reinforcing mechanisms start to exist e.g., coordination of information becomes easier as predictability increases. Organizational learning becomes formulaic. Decision strategies start to repeat themselves and a path starts to evolve.

Phase III: Lock-In: The organization is now constrained to a defined decision strategy: systems, capabilities and behaviours. Rigidity and inflexibility become prominent characteristics of the organization, which can impair its ability to respond to environmental changes or capitalize on new opportunities. While better alternatives may exist, the organization is now locked into a specific path.

Organizational Path Dependence: Opening The Black Box, Academy of Management Review, Jörg Sydow, Georg Schreyögg and Jochen Koch, 2009

Case in Point: Kodak

Kodak is one example of an organization that demonstrates the path dependency and its implications.

Kodak’s Surprisingly Long Journey Toward Strategic Renewal: A Half Century Exploring Digital Transformation in the Face of Uncertainty and Inertia, The Wharton School, Management Department, University of Pennsylvania, Natalya Vinokurova and Rahul Kapoor, 2022

The Paradox of Path Dependency

The paradox of path dependency lies in its logic. If a decision yields positive results, it is reasonable to use the same decision-making process again. Over time, this process becomes the default. The more success it brings, the more difficult it becomes to question or abandon it. Eventually, the process becomes institutionalized—even if the conditions that made it successful no longer exist.

It is rational to continue doing what works. Yet, that very rationality can breed rigidity. What starts as a strength—efficient routines, consistent messaging, deeply held values—can evolve into a blind spot.

Put simply, path dependency explains how organizations become locked into a way of doing things, often without realizing it. A decision made years ago, a policy written for a different time, or a success formula that once worked can shape how an organization thinks, acts, and responds—even when the environment has changed.

Avoiding Organizational Lock-In

1. Embed Strategic Consciousness Throughout the Organization: Stay attuned to subtle shifts—emerging technologies, changes in customer sentiment, or early signs of employee disengagement. Weak signals often precede major inflection points. Leaders must foster critical curiosity and regularly ask, “What might we be overlooking?” or “What are we treating as true that may no longer hold?”

Practical steps: • Incorporate this strategic sensing into hiring and leadership development e.g., use tools or scenarios that test how candidates respond to ambiguous situations and recognize leaders who challenge assumptions and embrace insights from younger or newer employees, and include in team and executive meetings discussion of “emerging shifts” or “latent risks” e.g., shifting societal and customer expectations or non-traditional competitors.

2. Operationalize Routine Reflection to Ensure Objectivity: Without intentional pauses, decisions become habitual. Reflecting on how decisions are made—not just what was decided—helps teams stay objective and avoid organizational autopilot.

Practical steps: • Use structured reflection processes for project and decision reviews, before and after approval e.g., post-mortems that can monitor response time and effort (people and money) required to make the decision and then conduct an external review with key stakeholders of strategic decisions.

3. Design for Elasticity as Well as Efficiency: Rigid structures are not always visible until they are tested. Flexibility must be built into roles, processes, and performance systems—not added on after the fact.

Practical steps: • Use staged KPIs to measure and manage flexibility and adaptability e.g., the number of new pilots launched, markets entered, response time to change, or employee suggestions submitted and tested and use of cross-functional teams and hackathons to respond to simulated business scenarios.

4. Experiment Beyond Current Business Logic: Not every idea needs to align with the dominant business model. Pilot teams and shadow initiatives can explore emerging possibilities in a controlled, low-risk environment.

Practical steps: • Establish clear criteria for experimentation—such as the potential to unlock new customer segments, challenge existing assumptions, or return value in a specific period of time, and maintain a pipeline of ‘quick-fixes’ that require the organization to use ‘out-of-the-box’ or exploratory methods for development..

5. Reframe Disruption as a Strategic Opportunity: Disruption is not only a threat—it is a reset button. It invites organizations to revisit their core assumptions and evolve their strategy in line with reality, not legacy.

Practical steps: Treat major disruptions as opportunities to question strategic assumptions e.g., customer value determined by price reliability, or shift of distribution network e.g., direct-to-consumer models and unconventional partnerships, and use these events to document what changed, what became possible, and identify existing models that may no longer be relevant to the organization

Diagnosing & Unlocking Organizational Lock-In

Identifying if your organization is in the Lock-In phase can start by evaluating how the organization responds to these same options:

Are decisions fast but rarely challenged? While this can create a sense of pride, it can also signal a reduction in critical thinking.

How is success defined? Do financial metrics dominate discussions of progress, while adaptability, learning and long-term positioning ‘fight’ for time on the agenda?

Has experimentation become symbolic? While pilots and test-and-learns exist, they are rarely the impetus for real change.

Does customer feedback feel inconvenient? Suggestions from customers or criticisms are dismissed as outliers or unrealistic.

Are disruptions responded to with defensive measures? Shocks are treated as temporary threats rather than catalysts for transformation.

If the response to these questions points to “Yes, we’re Locked-In”, then the next step is not to overhaul everything. Instead, the unlocking process should begin with deliberate and credible disruption to the dominant logic. The organization can introduce structured change to the dominant assumptions. This will need to be done with full transparency. Unlocking is achieved by making space for different thinking without declaring war on the status quo.

The SLG Project, 2025

Final Thoughts

As C.S. Holling reminds us, “…the management approach… would emphasize the need to keep options open… not the presumption of sufficient knowledge, but the recognition of our ignorance; not the assumption that future events are expected but that they will be unexpected.”

Organizations do not require a “…precise capacity to predict the future, but only the qualitative capacity to devise the systems that can absorb and accommodate future events in whatever unexpected form they may take .”

The greater risk is not making the wrong decision—it is becoming so attached to the right one that you forget when it stops being right.//

1. Tao Te Ching A New English Version, Stephen Mitchell, 1988. 2. Clio and the Economics of QWERTY, The American Economic Review, Paul A. David, 1985 3. Organizational Path Dependence: Opening The Black Box, Academy of Management Review, Jörg Sydow, Georg Schreyögg and Jochen Koch, 2009. 4. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems, Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, C.S. Holling, 1973. 5. Kodak’s Surprisingly Long Journey Toward Strategic Renewal: A Half Century Exploring Digital Transformation in the Face of Uncertainty and Inertia, The Wharton School, Management Department, University of Pennsylvania, Natalya Vinokurova and Rahul Kapoor, 2022. 6. The Dominant Logic: A New Linkage Between Diversity and Performance, Prahalad and Bettis, 1986, 7. Managing the Unexpected: Assuring High Performance in an Age of Complexity, Weick K.E. and Sutcliffe K.M., 2001, 8. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams, Edmonson, A. C., 1999, 9. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective, Argyris, C. and Schön, D. A., 1978 and 10. Ambidextrous Organizations: Managing Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change, Tushman, M. L. & O’Reilly, C. A., 1996.